In asking whether sociologists should have values or be value-free Howard S Becker famously asked ‘Whose side are we on?’ His conclusions were that we should be on the side of the powerless and oppressed: that as academics, social scientists had a duty to examine social structures and the effect they had on ordinary people.

At the time that was a significant challenge to the academy. Founded on principles of reason and rationality, most disciplines tried to represent themselves as free from moral or political imperatives. Particularly in the wake of World War Two, where German scientists and engineers were co-opted into carrying out science to further Nazi ideals, the independence of the academy from political taint was held to be vital.

However, what Becker was pointing out was that the academy does not exist in social isolation. It is part of the social fabric of a society: educating its elite, informing discourse and policy. We make moral and political choices all the time: in choosing who we educate and how, what we research and what we don’t. To claim moral neutrality in the name of academic independence is simply to hide the fact that we are part of the elite and reinforcing their power.

I work in social policy, specifically around issues of gender, disability and age. Feminism, disability rights and gerontology all have a moral and ethical framework that expects academics to challenge power relations: particularly to challenge misogyny, ableism and ageism. If in our research we do NOT aim to highlight and tackle oppression, then we are accused of being ‘academic parasites’: using people simply for our own reputation and to reinforce our privileged position. Many social science and humanities disciplines expect a critical stance from their academics: to examine and critique the world not just as we see it, but to acknowledge and reflect on our own place in the world we research.

So when I engage in research that involves gender, disability or age I always engage in it as a political process. I am not just interested in analysing the social policies pertinent to women, disabled and older people. I am interested in finding out what social processes oppress them, and how those can be tackled. And I always try to reflect on my own position in that research: not just as an academic, but as a woman, a disabled person and a carer.

Many academics are also activists. The campaigns against climate change, to protect endangered species, to prevent domestic abuse, to tackle racism in policing were all founded on academic research, to name but a few. Academics also have a long history of crossing the divide to the third sector – in my field the Fawcett Society, Inclusion Scotland and the National Carers Organisation have all been led by academics. There is also a long history of academics becoming politicians: Harold Wilson and Enoch Powell were former dons, and over 20 current MPs hold PhDs.

The current ‘impact’ agenda further supports close collaboration between activism and the academy: in the last REF, over 45% of impact case studies from my own discipline involved working with policy makers, and over half the universities entered reported ongoing collaborations with the third sector. Evidence-based policy and practice attempts to use research to inform social policy in proactive ways, and academics are usually very enthusiastic about its possibilities.

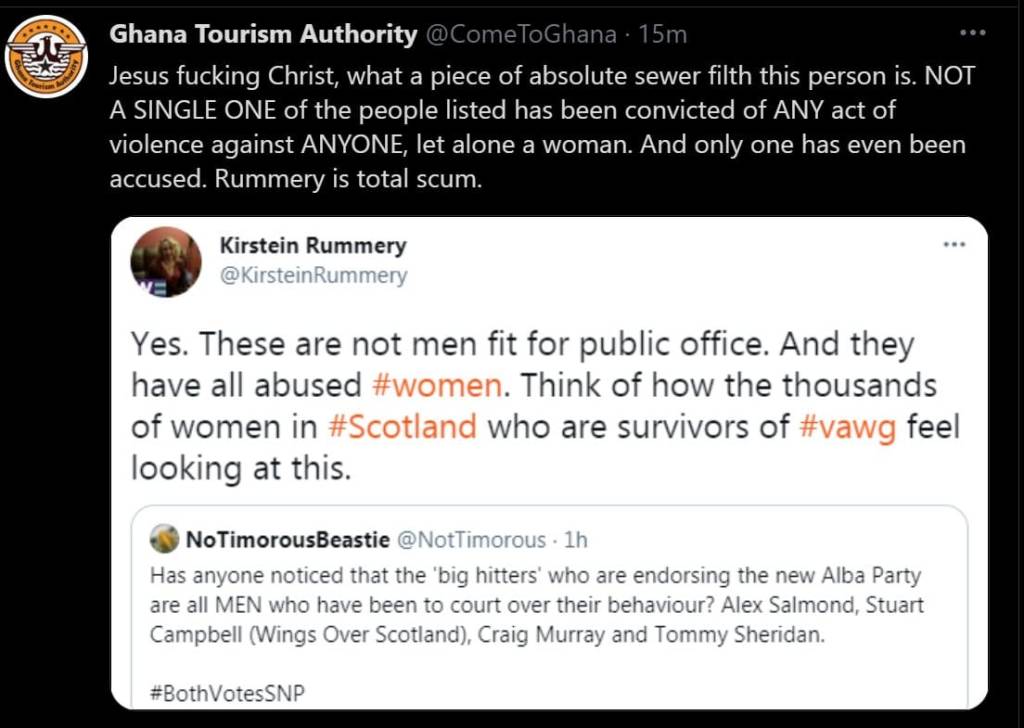

However, activism has its dark side, particularly in the age of social media and the resurgence of right-wing politics. As an openly feminist woman in academia I attract the usual misogynistic attacks in mainstream and social media. During the 2014 Scottish referendum I was carrying out independent research funded by the ESRC on what the different outcomes might mean for care policy and gender equality. I found that nations who had better gender equality outcomes, and used social care policies for that purpose, had gender equality enshrined as a national value in their constitutions. As a potentially newly independent country, Scotland could have that, and thereby acquire a powerful lever to effect policy changes. (Of course that alone would not make an independent Scotland a gender equal country and I was careful to stress that too). This finding marked me as a politically motivated independence supporter (I wasn’t) and attracted a fair amount of social media attacks from ‘cyberyoons’ (social media commentators against Scottish independence). Some took the trouble to track down my institution and make a formal complaint – which luckily my institution carefully replied to in my defence. I took it as a mark that I got ‘cybernatted’ almost as often as I got ‘cyberyooned’ that I was getting the balance of academic impartiality about right.

When I recently crossed the divide from activism to politics and ran for election in the 2017 snap general election, representing the Women’s Equality Party, I did so to highlight the gender-blindness of the main political parties. I campaigned on areas I knew about: social care policy, violence against women and women’s political representation. I was stalked, harassed, had frighteningly explicit pieces written about me in newspapers, and one men’s rights activist issued death threats on his website and targeted not just me but also my colleagues and students.

It’s hard to say whether that was because I was a woman, or a feminist, or a politician (all of whom regularly are the victims of hatred on social media). But my political opponents in particular hated that I was drawing on 25 years of research in my campaigning. In one hustings, after I had criticised the ‘dementia tax’ policy of the Conservatives, my opponent shouted at me ‘NO-ONE KNOWS THE SOLUTION TO SOCIAL CARE, NOT EVEN THE SO-CALLED PROFESSOR!’. Actually, I do know A solution based on years of comparative social policy research, and I earned the title ‘Professor’ through my international reputation for my research. But hey, all’s fair in love and war and politics.

Clearly as a society we value academics getting their hands dirty and engaging in the real world. The ESRC funded me specifically to find real world solutions to real world issues to help policy makers prepare for possible constitutional change, not sit in an ivory tower writing academic theories that no-one outside the academy would read or understand. The current REF will apportion 25% of its research funding on the basis of the non-academic impact the research has. We want and need our academics to use their knowledge for the greater good, and sometimes using that knowledge is a consciously political act.

But we need to protect them. If we value their expertise and their independence, we need to ensure that they are able to not just research the risky subjects, but take the risks necessary to get their findings into policy and practice. Academics should never be censured for taking activist or political positions on things they know about.

However, as academics we also have an ethical and moral responsibility to not step outside the boundaries of our research or claim knowledge we don’t have. The current problems with Personal Independence Payments for disabled people can be directly traced to psychological academic theories being misused in a social context. The depiction of Scottish independence supporters as far right nationalists can be directly traced to a misuse of political and historical theory about nationalist movements particularly in the twentieth century. The list goes on.

We should expect protection from our institutions and from society, we should fight for the things we know to be ‘true’ based on our research, we should fight to keep our independent critical stance. No matter what Michael Gove thinks, we need experts now more than ever in tackling some of the complex social issues that face our society. But we should not claim to be experts in everything or to have the ‘right’ answers, or to think that our status as elites gives us permission to ride roughshod over the electorate, or third sector activists, or people who are experts in things as a result of their lived experiences. We should lend our expertise to amplifying their voices: we SHOULD still be on the side of the oppressed. Otherwise we are simply reinforcing our own privilege.